Akebono: Navigating Automotive Supply Chain Challenges

Akebono North America aims to get ahead of supply chain issues whether man made or natural disasters.

By Mark Lawton, Senior Editor at Knighthouse Media

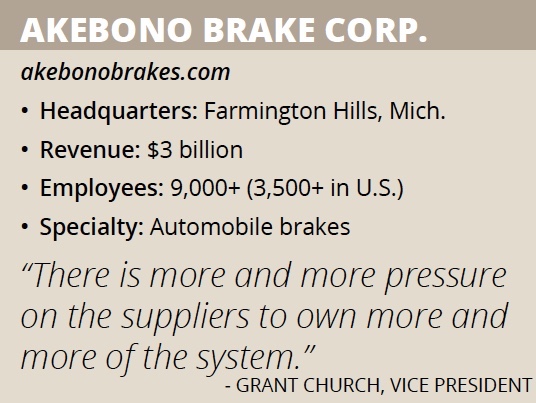

Akebono’s automotive customers expect just-in-time delivery of brakes and parts. “There is more and more pressure on the suppliers to own more and more of the system,” Vice President Grant Church says. “In the old days, the customer would pick up at the dock and deliver to his own buildings. We are often asked to take on that responsibility. “

“Sometimes we amortize the [returnable] containers into the price by the piece so they don’t have to tie up working capital. The expectations for quality and delivery keep going up.”

Fortunately, Akebono has a long history of meeting expectations. The firm was started in 1929 in Japan, back when the Japanese auto industry had produced a mere 400 vehicles. Today, Akebono employs more than 9,000 people worldwide, with over 3,500 employees in North America.

In Japan Akebono supplies brakes for about 40 percent of all vehicles; in the United States it supplies a little under 20 percent of the market.

Akebono operates R&D technical centers in the United States, Japan and France, and manufactures brake friction materials and components in 30 wholly owned or affiliated facilities worldwide. Among those is the North American Brake Systems Engineering Center in Farmington Hills, Mich., which it opened in 1989.

At the Farmington Hills engineering center, engineers simulate the torque and energy created by a vehicle system and how it impacts the vehicle’s brakes. “There is a sound-deadened room,” Church says. “You can hear every click and rattle.”

Managing Risk

The engineering center also hosts part of the supply chain risk management team of Akebono North America; the other members are in Elizabethtown, Ky. The team aims to predict natural disasters or man-made issues that could interfere with suppliers and create a work-around strategy. Protecting the original equipment via risk management is part of the increased ownership of the supply chain.

Take Hurricane Harvey in August 2017. The risk management team knew that a supplier in Texas was likely to be hit.

“We had a good idea how exposed we are,” Church says. “What we will typically do is look at our inventory and customer demand for that product and come up with a parts bank strategy. We’ll contact the supplier and find out how much product can be built and shipped out before the natural disaster occurs.”

A hurricane, which gives Akabono several days lead-time, is not as tricky as an earthquake or other natural disasters where they have little or no warning. In those cases, the risk management team might contact an alternative supplier and seek authorization from its automotive customers to changes sources or expedite shipping.

Man-made issues present other challenges. One instance is when a Longshoreman’s union contract is up for renewal and there is the possibility of a strike – something the risk management team tracks.

“If there is a Longshoreman strike in California, we have to ship to Mexico but the supply chain is restrained,” Church says. “More shipping is diverted to open more and more trucks moved farther over the border.

The team also monitors more subtle indicators of how their suppliers are doing. Financial issues can be telegraphed by quality and delivery issues.

“There are situations where suppliers have quality and delivery issues,” Church says, “where they are not taking care of capital equipment. You’re more likely to get parts late. Then the suppliers get behind and they skip steps and quality goes downhill. Or suppliers start to have more turnover – the sales guy, the plant manager, the quality control guy – when they are having trouble with quality control.”

“Sometimes you are actively working with the supplier [to resolve the issue],” he adds. “Sometimes the supplier is the problem.”

Eyes on Tariffs

The risk management team also figures out how to respond to tariffs.

“Most people don’t understand that when tariffs came in, the domestic market in the United States went up,” Church says. “[The domestic market] went up higher than the tariffs placed on foreign steel.”

And that’s a real issue for Akebono North America.

“Most of our suppliers are domestically sourced,” Church says. “The tariffs have driven the U.S. market price point way above the global market. It’s a lead-time issue. [Foreign steel] has to be loaded on ships and then unloaded and then put on trains.”

One solution is to keep a close eye on contracts.

“A supplier will come to you if there is an increase [in his costs] but not if there is a decrease,” Church says. “You need rules of engagement. In an upward market, you want a longer-duration contract with your suppliers. It’s not just about monitoring your supply base but how you structure supply agreements.”