Boston Scientific: Saving Lives Through Supply Chain Excellence

Boston Scientific benefits from its centralized supply chain.

By Alan Dorich, Senior Editor at Knighthouse Publishing

At the hospital, we want to feel secure that the devices needed to provide us with care will be there. Boston Scientific Corp. focuses on ensuring those items are in the right place at the right time when caregivers need them, Senior Vice President of Manufacturing and Supply Chain Brad Sorenson says.

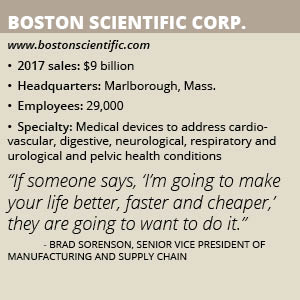

Based in Marlborough, Mass., Boston Scientific started operations in 1979 with the goal of bringing more accessible, lower-cost and less invasive options to patients. Today, it sells a wide range of products to healthcare providers, including balloon catheters, defibrillators, pacemakers, urology products, needles, lasers, forceps, catheters, spinal cord stimulator systems and stents.

“We have a unique ability to connect our employees to our culture because we do serve patients,” he says. “The products that we make either improve patient lives or actually save lives.”

A Caring Culture

Sorenson joined Boston Scientific more than 20 years ago after working in the ammunition industry. The ability to save lives, he notes, drew him to the healthcare industry and the company, which helps treat more than 25 million patients annually.

He adds that Boston Scientific’s employees are guided by six values in their work: meaningful innovation, caring for patients and employees, high performance, global collaboration, diversity and a winning spirit. “Our employees really live the culture,” he declares. “It’s not just a set of words.”

The ability to help people heal has given Sorenson personal rewards, including the feeling that he is answering a higher calling. “I truly know what I’m doing is impacting somebody’s life today,” he says.

Aiming to Lead

Boston Scientific has 13,000 products in the core areas of endoscopy, interventional cardiology, neuromodulation, peripheral interventions, rhythm management and urology and pelvic health. “Our focus is to be No. 1 or No. 2 in the markets we serve,” Sorenson says.

But being a leader can bring many challenges from a supply chain perspective. This has required Boston Scientific to have a broad breadth as it sells core products and all the peripheral items that support them.

“We don’t get the luxury of picking and choosing and saying, ‘We only want to play in the big behemoth parts of the industry,’” Sorenson says. He explains that the company’s supply chain needs to be flexible in terms of product numbers, differences in volume and rates of usage.

Another challenge for Boston Scientific is how it sources components and materials. The length of time to get regulatory approval and how long the products remain in the field “means we have to develop long-term partnerships with suppliers,” Sorenson says.

“When we partner with a supplier, it is for the long run,” he continues. “It forces us to think about our supply base differently than a consumer electronics company.”

An electronics company, he notes, can switch suppliers easily. But Boston Scientific has to form relationships that stretch across the development and clinical trial stages to commercialization. They also must operate across multiple geographies, where requirements can be different.

However, the company has historically been quite successful at forming these relationships, Sorenson notes. Today, Boston Scientific has 900 suppliers it manages. “Each of them is absolutely critical to our business,” he asserts.

Evolving the Chain

Over the past two years, Sorenson has focused on improving Boston Scientific’s approach to managing the supplier partners in the supply chain. Previously, he explains, the system was very decentralized and managed differently across the various business units and manufacturing locations.

Sorenson’s team historically managed the actual purchasing, logistics and relationships, but they were not included in the decision-making when it came to selecting suppliers. “Divisions, regions and plants often made and executed decisions on what to buy and who to buy from locally,” he recalls. This created a lack of leverage and consistency in suppliers.

Since then, Boston Scientific has moved to a system where vendors have a single point of contact. This was managed by centralizing the functions of supplier management and supplier engineering, Sorenson says.

But the company took careful steps before making drastic changes, Sorenson notes. The company initially moved some of its employees into the centralized structure and invested in supplier engineering and supplier management resources.

It also provided consultative support to its divisions. “We stepped in, added resources, [and] showed them what good could look like,” he recalls. “[We told them], ‘We believe a long-term, centralized approach is better and we’re investing to prove it to you.’”

Sorenson and his team also walked Boston Scientific’s leaders through the process and reinforced that what they were doing was for the better. “If someone says, ‘I’m going to make your life better, faster and cheaper,’ they are going to want to do it,” he says.

Ultimately, he won the approval from Boston Scientific’s CEO as well as the full executive committee. “If you’re going to [do] this type of fundamental culture change or shift, this is a bit of change management 101,” he advises. “You have to get the buy-in from the top of the organization or no one is going to want to be the guinea pig.”

The New Normal

Boston Scientific has successfully transitioned to the centralized structure, Sorenson says. Although there were some challenges along the way, the company benefited by selling the value proposition of the change to its associates and explaining what it was going to do early on.

All employees, he notes, knew what it would look like at the end and were committed to getting there. “To have gotten to where we are in two years and … where this is the new normal I think is impressive,” Sorenson says.

Today, Boston Scientific has a leader for each of the 60 specialized commodities it sources, such as plastics, integrated circuits and metal components. Those leaders, Sorenson explains, look at what the company buys and whom it buys from.

The supplier engineering leaders, he continues, align with the supplier management and look at the technologies the commodities go into. They also work directly with R&D and manufacturing to sure the company has the right components and technologies. Both of these teams report directly to Boston Scientific’s vice president of global sourcing, so they remain connected.

“This has created a one-two punch,” Sorenson says, adding that the company can better develop supplier relationships and leverage its buying powers.

“We’ve hardwired all the sourcing decision-making authority for new product development within the divisions,” he continues. ”The divisions are finding it actually accelerates product development for them.”

Essential Reductions

The centralized system has allowed Boston Scientific to reduce its supplier base by 15 percent. Sorenson asserts that it is essential in the firm’s regulated industry to visit every supplier annually and do a formal audit.

Going from more than 1,100 to 900 has taken hard costs out of Boston Scientific’s system. But it also has enjoyed a more than 6 percent standard cost improvement year over year by moving to more strategic vendors, he says.

Boston Scientific also has seen improvements in supplier performance, which was previously a challenge for the company when it had more vendors. “When you start taking the tail of the distribution off on those phase-out suppliers, that improves the performance and quality,” Sorenson says.

The system also supports Boston Scientific’s move into emerging markets. The more consolidated approach, he says, creates better connectivity for the company around the world.

“By doing it from a centralized perspective, we can feed emerging markets with the same capability we use to feed the U.S. market,” he says, noting that this prevents Boston Scientific from thinking about each market differently. “We’re a bit agnostic because we manage it as one global system.”

Motivated to Excel

Boston Scientific today ranks its suppliers in four separate categories, Sorenson says. On one level are its strategic suppliers who are characterized by leading-edge technology that creates a competitive advantage for Boston Scientific. These suppliers have early involvement in the new product development process. Its preferred suppliers, who are typically not as technically advanced but are committed to the medical device business for a long time and have business goals aligned with the company, comprise another level.

The company also has its standard suppliers who provide more commoditized materials and those who are on restricted-phase out status, due to quality or performance issues. Although Boston Scientific may potentially buy more of their components, he says, they are moved to a status where the company does not do any new business with them.

Boston Scientific does not shield the suppliers from these rankings. “All our suppliers know where they stand in that process,” he says. “We do this with full transparency with our supply base.”

This information, Sorenson explains, can drive the suppliers to improve their performance and move up in the ranks. Boston Scientific also tells its strategic suppliers that it expects them to show proactive support in developing technology.

“That’s why we try to be transparent,” he says. “We see it does motivate and drive many vendors, suppliers and partners.”

Eye Openers

Boston Scientific recently aligned both direct materials (materials that go into product) and indirect materials such as consulting spend, IT spend and travel under a dedicated vice president of global sourcing. This, Sorenson says, will allow the company to select, manage and think about suppliers in a more strategic fashion than just as a provider.

“It has huge synergies for us from a quality of service and cost perspective,” he says, noting that the company wants to give its supply chain professionals more opportunities to develop their careers as it moves people between direct and indirect sourcing.

Boston Scientific recently partnered with Corp U and Penn State Smeal College of Business to develop an intensive supply chain-training program to create opportunities for development. When the company began centralizing its supply chain, “It became apparent that people across the organization didn’t do things the same way,” Sorenson recalls.

So far, Corp U has had more than 100 participants annually who learn about the supply chain. “It truly opens people’s eyes up to what’s happening in the organization,” he says. “As a result, people start making better decisions because they have a better idea of how the organization operates. It’s created a common language across the supply chain to support execution of priorities and drive supply chain excellence.”

Far from Finished

Sorenson is proud of Boston Scientific and the work it has completed with its supply chain. “At the end of the day, supply chain for us is not just moving boxes,” he says. “It is about us serving patients.

“Because of what we do, people’s lives get improved or people’s lives get saved,” he says. “I’m incredibly proud that we treated 25 million patients last year.”

But Boston Scientific has more work to do. The company is focused on forming better connections between its planning, sourcing and delivery departments, Sorenson says.

“We need to make sure all of those groups are truly integrated in a supply chain that goes across our plan to what we’re delivering to the customers,” he says. “The passing of information [needs to be] seamless.”

The company’s recent hire of its vice president of global supply chain, Terrance Brick, will help insure that. The associate is responsible for all the planning, sourcing and distribution. “That’s the connection now between those different groups,” Sorenson says.

Well Prepared

Boston Scientific’s supply chain has proven itself to be functional even in the face of disaster. The company, which has a large footprint on Puerto Rico, found itself working in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria last year.

But Boston Scientific had prepared itself before the disaster. “Ahead of that storm, we strategically front-loaded inventory,” Sorenson recalls, adding that it frontloaded many generators, components and materials both into and out of the island.

The company, he adds, also had the infrastructure in place to deal with it and moved people around the globe to be ready for it. “At the end of the day, we did not miss a single case due to supply interruption in Puerto Rico,” he recalls.

“We were back up and running within a week,” Sorenson says, noting that the company was back at full capacity within a few months, even though there are still some parts of Puerto Rico without power today.

The incident, he notes, was a great example of planning and execution for Boston Scientific. “The real test of the supply chain is when you have a major disruption like this,” Sorenson says. “Then you find out if it works.”

Helping Hand

Boston Scientific also helps patients through its giving programs that are designed to provide improved education and healthcare to members of its communities. These include grants and donations that support independent medical research, educational programs and charitable projects.

The company also funds non-profit, health and education related organizations through the Boston Scientific Foundation. It places “a specific focus on at-risk communities and removing barriers to access of care,” Boston Scientific says.