Revolutionizing Procurement: Biogen’s Big Data Analytics Journey

Biogen is rethinking its procurement processes by relying on ‘45 second analytics’ to quickly select quality suppliers.

The idea of procurement elicits images of boxes moving on conveyor belts, trucks traveling interstate highways and new supplies or equipment arriving at a warehouse. But for biotech firm Biogen, people are as important as any other resource the company procures. Each time Biogen brings a new medical therapy or drug to market the company needs to find patients willing to participate in a study of the treatment.

If the company is conducting trials on a drug to treat Alzheimer’s it needs to find people who suffer from cognitive challenges, such as leaving their keys in the car or driving away and then forgetting where they are headed. To find those people, the company hires a supplier who recruits and supplies the people for the study.

That recruitment effort can take a few forms. The supplier might hold a wide sweeping media campaign inviting people who suffer from cognitive issues to participate, but the advertising blitz is an expensive option. Another route is to select a supplier who can leverage their relationships with doctors to recommend patients who meet the study’s parameters.

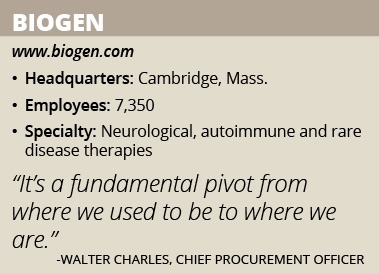

Either method results in Biogen getting the 2,000 patients it needs, but each has a different cost. Biogen selected a supplier who took the latter route for a recent study and saved $9.5 million. Chief Procurement Officer Walter Charles says that kind of savings was possible because Biogen is using big data to analyze its sourcing and expand the number of suppliers it considers. “If you get more suppliers in the game you create friction,” Charles says. “Friction creates heat, heat creates lift and lift creates savings.”

Having a wider range of suppliers to look at means companies can better understand where they can improve their specifications and surface level agreements, Charles adds. Why force the use of a specialized packaging with a longer shelf life if a less-engineered plastic wrap will do the job, for example. Knowing where those requirements will handcuff the supply chain allows the procurement team to discuss with the rest of the company about whether those specifications are worth millions more to implement than the alternatives.

To truly realize the savings of that philosophy requires the capability to consider all possible suppliers. But how can that be done when there’s a planet full of suppliers, and companies are limited by the manpower of their procurement teams? That’s the challenge Charles is solving through big data analytics.

Shifting Approach

Charles has extensive experience in bringing new thinking into the supply chain. He earned an MBA from Columbia Business School and holds several engineering degrees. “I like solving problems, but I like solving problems that actually matter,” he jokes. Before joining Biogen in September 2015, Charles was the chief procurement officer for Kraft Foods, Kellogg’s and Johnson & Johnson. It was at Kellogg’s where Charles began implementing his version of big data driven analysis for procurement, a process he calls “45-second analytics.”

The idea is that one person with access to robust data can analyze a procurement scenario in a few seconds compared to the traditional process, which can take weeks or months. Since the process goes faster, the procurement team can analyze hundreds more suppliers for the same job, giving the company a far wider range of options and more actionable insight.

Although the businesses cover different industries, Charles says the pain points in the supply chain for Biogen are the same as other companies. The goal is to save money in sourcing no matter what. In most cases, that requires hiring more people to do sourcing and supply chain analysis to realize those larger savings. That model is time consuming and relies on having a large staff. One way around that limitation is through better technology.

Procurement departments do a great job of obtaining technology for the rest of the company, but Charles says they don’t do enough for their own needs. “If you’re going to spend millions you want to make sure it’s going to deliver,” he explains. “We [procurement people] are the most cautious group of naysayers anywhere.”

When Charles was learning about procurement the entire process – including supplier analysis – was done using Excel. The capabilities of the program don’t fit the kind of disruptive, data-driven analytics Charles envisions but 99 percent of all procurement is still done using that well-worn process, Charles explains. The slowness and the difficulty of performing an analysis using spreadsheets forces procurement teams to narrow their scope and work with fewer potential suppliers to make the task manageable. “We deliver our savings number, but there’s much more value to be unlocked if you can deliver the cost drivers of what you are buying,” he says.

Vision for Data Analytics

Today’s technologies and systems are allowing companies such as Biogen to implement procedures that dramatically cut down procurement cycle times and do more with fewer people. Charles says it is a question of how to apply those technologies so teams can get more done more robustly. “Instead of boiling the ocean, I’m going to focus on where the money is,” he says.

Charles imagines what the procurement process would be like if it were unencumbered by the manpower needed for analytics. Companies could analyze 1,000 potential sources as easily as six, granting a better picture of all the sourcing possibilities to make better decisions. “It’s a fundamental pivot from where we used to be to where we are,” Charles says.

There are a few sass-based solutions Charles is using to achieve his vision of big data analytics. But just as important, big data analytics requires a meaningful methodology change to implement. “The big gap becomes not the tool but the method that you follow to extract value form the tool,” he says.

Key changes to the process include clean sheeting, an approach that involved modeling the production cost of an item for negotiations. Biogen also practices an alternative to funnel bidding, which seeks to reduce the pool of potential suppliers. Instead, the company follows what Charles calls “funnel-less bidding,” a fact-based process that encourages a high-number of initial bids and eliminates suppliers based on bid performance.

Charles believes the use of big data will disrupt the bidding process the same way Uber has disrupted the taxi industry. He’s already seeing evidence of its success. Implementing 45-second analytics resulted in 40 percent to 60 percent savings for Kraft, Kellogg’s and Biogen, equal to about $8 billion. Further, being able to analyze more suppliers gives insight on emerging business models and helps Biogen stay ahead of shifts in the market. Having that data available has made the procurement department a better consultative partner with the broader business and helps them show the cost consequences of purchases. That can lead to compelling conversations about alternative options, Charles says.

Using the big data analytics approach saved Kellogg’s $113 million in the first 120 days, and saw a 190 percent improvement in procurement spend the first year, Charles says. It also helped Kraft completely rethink the way it sourced products. When Charles was still at the company, the food maker’s labels contract was expiring. Using traditional methods, Kraft would have limited its supplier pool to 10 usual suspects and sourced labels for each of its production facilities separately, even if the chosen provider was the same. But through 45-second analytics, Kraft looked at 900 potential suppliers for 5,100 SKUs. It ran 172 scenarios that considered things like pricing, capacity, automation and whether a business was veteran owned to evaluate each of those suppliers in seconds. A detailed analysis that would have taken two-and-half months under the old model was completed in less than two days.

This year, Biogen is targeting a 250 percent improvement over its historical procurement rates. Charles sees even more significant gains in the future. With faster analysis, the function of procurement will shift. If a two-month bidding process can be condensed into a few days, the procurement team’s focus can be shifted to higher value goals.

Eventually, the time savings from analytics will become the onramp for the next generation of procurement processes. Charles sees a future where commodity items such as coffee beans or medical supplies are entirely automated. Instead of needing a human employee, a machine like IBM’s Jeopardy-winning Watson could conduct a detailed analysis and spit back an answer using a plain language interface. “That’s what I believe at a high level the journey is,” Charles says.